As historians, we are taught to utilize primary sources. In fact, our work is only possible through accounts, whether written or visual, of past events. However, our whole field of work becomes unhinged if the very primary sources we study are doctored. I don’t just mean relying on a diary that has a biased perspective, but basing historical work on a source that is fabricated or changed to create a different meaning. This becomes particularly disheartening when photos, the seemingly most truthful depiction of history, is the product of political objective.

Some photographs have now been identified and discredited for their edits. Yevgeny Khaldei’s “Raising a Flag Over the Reichstag” taken in May 1945, seems to capture the triumphant moment Soviet forces freed Eastern Europe from the grips of Nazi control in the capital city of Berlin. Much like Joe Rosenthal’s photo of soldiers raising an American flag over Iwo Jima, Khaldei’s photo depicted the moment good seemingly won over evil. Perhaps this is due to some crucial edits and staging of the photo. Though Khaldei took great care to make a Soviet flag big enough to recreate the patriotism of Rosenthal’s photo, he failed to realize that one of the soldiers in the picture was wearing a watch on each wrist – physical proof of the rampant looting Soviet troops committed in military occupations. Soviet censors order him to remove one of the watches before it was to be printed in major newspapers. Only with the confession of Khaldei, vast knowledge of the propaganda strategies of the Soviet regime, and original prints can historians definitively mark this photo as evidence of the corporation in the Soviet Union’s totalitarian regime.

However, is this photo really just the product of totalitarianism? Quick to prove political intentions, we can forget the photographer himself. Nazi forces killed most of Khaldei’s family and he witnessed the atrocities German forces committed in Eastern Europe throughout his own life. So while Khaldei had government orders to doctor the photo, he had his own reason to make the Soviets look like heroes over the evil of Germany. In fact, he would deflect questions about the photo with answers like “it is a good photograph and historically significant. Next question please.” Both groups wished to elevate the Soviet image, but different reasons.

So, does it matter that the historical record gets the right intention? Filmmaker Errol Morris thinks so. In his New York Times article covering his efforts to discover which photo of “The Valley of the Shadow of Death” came first by Roger Fenton, he criticizes the psychological analysis experts revert to in order to prove that Fenton initially moved cannonballs onto the road to create more dramatic image. Many cited that it was “obvious” Fenton moved the cannonballs back on the road for a better shot. Even though Morris was wrong and the cannonballs on the road was in fact the second picture, the intention was not as obvious as others believed.

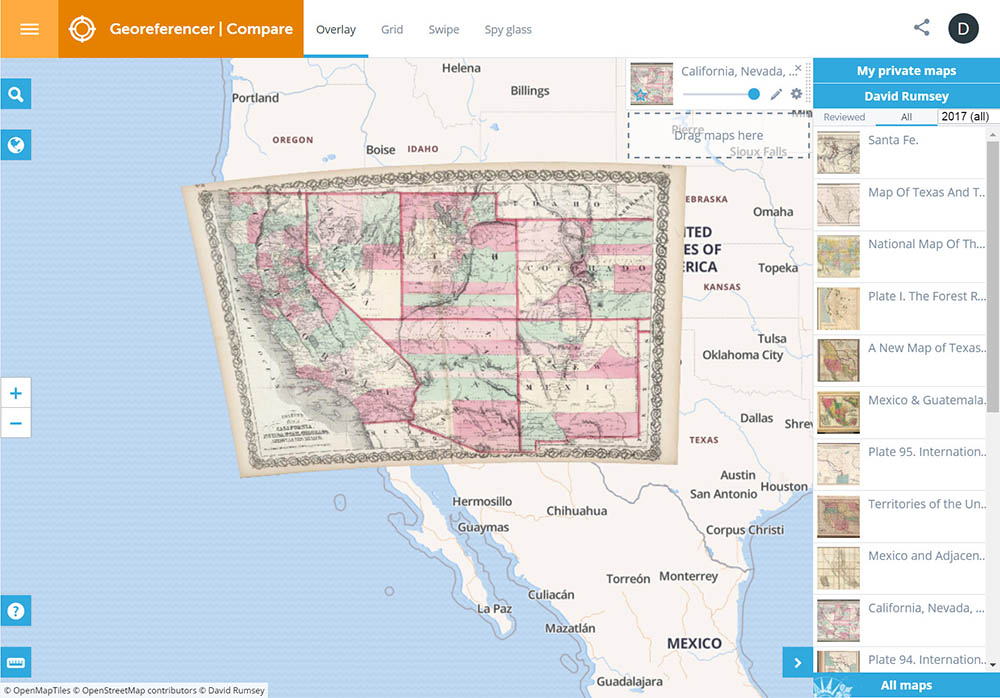

Therefore, sharing data and visualizations of the past cannot fall victim to the human tendency to go with the obvious explanation. What seems obvious to us now would not seem obvious to actors of the past – and vice versa. We as historians must provide the tools and insight in order to overcome our own biases through lived experience. Programs like Georeferencer v4 let people compare modern understandings of the world around us versus the understandings of those before us. Looking at a current map over top a historical map from the 16th century could enhance our interpretation of Early Modern navigation and worldview. Tools like this will allow us to view visualizations of the past in their own time, rather than creating a historical narrative based on what we perceive to be obvious.

Viewing visual primary sources in their own time does not mean we have to adopt the prejudice or ignorance of a previous society. Rather, it means in order to gauge the most truthful depiction of the past, how society was perceived in its own time, we must set aside what we assume is obvious to what those before us were just experiencing.

6 replies on ““Nothing is so obvious that it’s obvious””

You make a lot of excellent points here, and the title of your post was a line from Morris’s article that stuck out to me as well. Is there a risk that questioning too many “obvious” details might be a bad thing? While I think that it’s ultimately beneficial to question as much of a source as possible, I’m curious that if historians might miss the forest for the trees in some instances.

That is a valid concern. Morris himself even warns about the power of conspiracy theories. In some instances, they might seem silly and completely irrational. However, in cases like claiming the massacre of 20 school children and 6 teachers in Sandy Hook was fabricated by the government in order to achieve stricter gun laws, these theories have immense harm on personal lives and the course of historical memory. “Questioning the obvious” can truly be used for evil purposes, as we can see throughout history. I think there is a fine line for us to balance in our own work.

I believe that as historians, we have to view any primary source with a grain of salt. The Soviet Union under Stalin’s leadership is full of doctored photos used for propaganda purposes or reflection of Stalin’s paranoia. Another popular Soviet picture is of Stalin, Molotov, and Nikolai Yezhov at the Moscow Canal. Yezhov would be removed from the photo after he fell from Stalin’s favor in 1939. This begs the question, how many more historical primary sources have been intentionally altered to fit a narrative set by the ruling regime? While modern pictures are a easy example, how does one explore sources that are thousands of years old? Do we take the information on the nose or as historians should we analyse the source in tandem with other primary sources to paint a more “truthful” picture of the past?

I like your reference to Yevgeny Khaldei’s “Raising a Flag Over the Reichstag” photograph! It’s a great example of visual doctoring that I hadn’t thought of while reading.

When you said- “what seems obvious to us now would not seem obvious to actors of the past – and vice versa,” it reminded me of that phrase “hindsight is 20/20.” But that foregoes what would be obvious to the people living in the past and their what their perspective was.

Since history seems to be a matter of time and perspective, I would assume then that not taking into the account of how people felt then would not be a historian-esque thing to do. However, it would be easy to do from our innate tendency to bias. Although bias can have negative repercussions in most- if not all fields, I would be willing to argue now that it’s particularly critical in the realm of history. Because as your title states, “nothing is so obvious that it’s obvious.”

Reading the article, this quote also stuck me, for different reasons. I am usually missing the obvious in everyday life, so what may be obvious to one person may be coming completely from left field to another. We can only prove what is written, but not the intent behind the writing. Same with photographs. A photograph was taken, but how much of it was staged, and how much of it was not? Where does the line appear? Is a photograph staged when a subject is told to smile? That smile might be completely fake, but they gave a smile because they were asked to.

No one doctors a photo without a reason, even if it is to defame or remove something, there is a reason for that. There is a reason to add details or change colors, meant to improve clarity or make it prettier.

What about photographs were color was added in later?

This was an amazing, thought provoking post! I really appreciated your inclusion of another example of a photo that had two versions, and how you compared and contrasted each situation. Intention definitely matters in history, and knowing the intentions behind doctoring photos is important for understanding complicated historical events such as war, and the ways in which societies have interpreted and presented the horrific injustices of wartime to their respective public.

I do think that we as historians and as knowledgeable citizens should be careful about jumping to conclusions regarding the intentions of historical actors. Your post really made me think of this, showing the difference between a photo set that had not been doctored and was just the result of happenstance, and a photo set doctored for political purposes. The historians discussed in Morris’s article seemed to immediately assume intention behind the photos, and while their conclusion about which photo came first was correct, they were overthinking Fenton’s intent behind the photos. As discussed earlier in the comments on this post, conspiracy theories are rampant in our society and can often go far astray from the real truth behind events, skewing interpretation of them for years to come. This can be dangerous for historical memory and the work of historians in future, looking back on events such as 9/11, the Sandy Hook attack, and Kennedy’s assassination, among other events.