This week, participants in HIS 5595 explored how historians use data and visuals to make sense of their research. Each table received visual explanations and participants discussed the relationships established by the data, which data is displayed (and which is absent), and the purpose and intended audience(s).

The first graphic – Minard’s 1869 map of Napoleon and his army’s march through Russia – provided an array of helpful information. The build-up to the Franco-Prussian War meant that Minard created this map as a warning for French audiences in 1869 to remember the follies of imperialistic ambitions. The graph packs a lot of data, which shows casualties in relation to temperatures, time, space, and geographic locations of importance.

The second image – Reebee Garofalo’s The Genealogy of Pop/Rock Music – is a somewhat subjective measurement of how earlier genres could birth new forms of rock music. As fascinating as these relationships seem to the casual viewer, participants largely agreed that that Garofalo’s use of record sales was not as well documented. Also, the diffusion of music is not very well explored, such as the effects of transistor radios, along with the home audio system becoming economical enough for the middle and lower classes. All of this leads to more sales, yet these technological advancement were not measured by the graph. That being said, her work is a fascinating look at how trends in music birth new sounds and styles.

The rest of the session dealt with a variety of graphics and images, including: an illustration that explains “Why the Potomac River Is So Dangerous,” which provided an excellent explanation of the dangers of navigating the Potomac (even to the point where text could be removed and still reach multiple cultures and languages with ease), another illustration that teaches viewers how to spot hidden handguns (presented by a former law enforcement officer ), and a historical graph that provides a beautiful representation of world empires and their offspring.

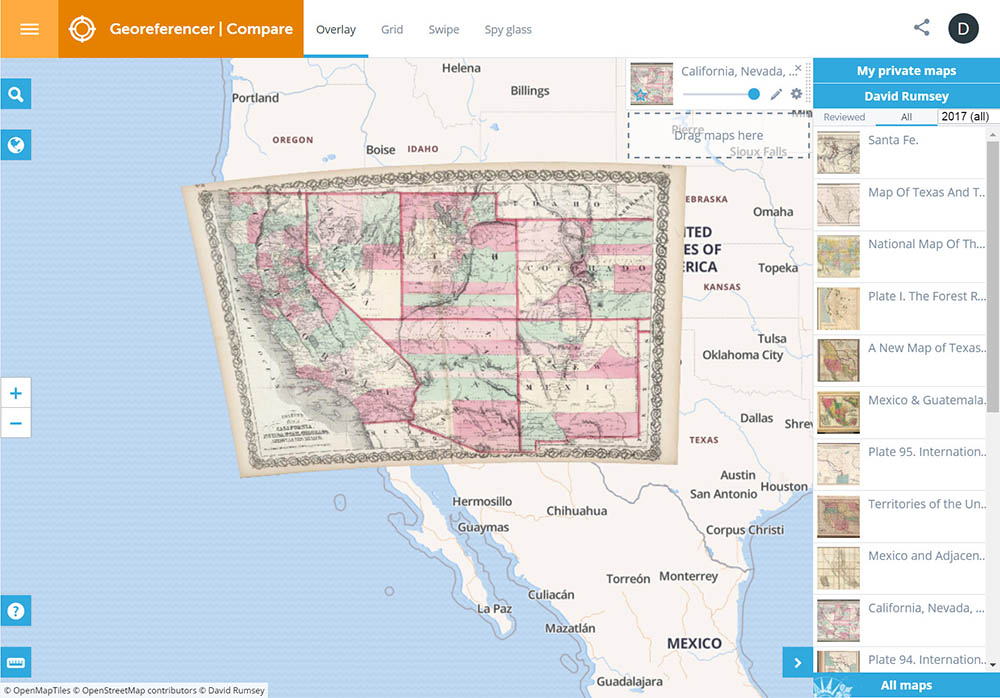

We also explored various mapping models (Mercator, Gall-Peters, etc.) and their inherent biases, GIF images that chart the history of slavery to the Americas and the loss of territories of indigenous peoples in North Americas, as well as the website Renewing Inequality, with a variety of visualizations detailing income inequality in the United States. This last website – Renewing Inequality: Family Displacement through Urban Renewal, 1950-66 – allows viewers to explore how people were displaced based on skin color, poverty, location, and type of displacement. It is an immersive experience, one matched by the website Foreign-Born Population: A Nation of Overlapping Diaspora, which allows users to explore immigration to the United States by county. It provides the number of immigrants and their country of origin.

Session 6 ended with some levity, of sorts, by looking at how Google Maps sparked a political conflict between Costa Rica and Nicaragua, the London Underground map (and how the metro lines actually run on a physical map of the city), and filmmaker Errol Morris’ in-depth analysis of photo manipulation by Roger Fenton during the Crimean War in his photograph “Valley of the Shadow of Death.”

–-Josh, Jeff, Kaitlyn, and Lydia