The story of Digital History has to cover the relutance with which some other academics in the history discipline have, or have not, accepted the field. Some historians fail to see how the field progresses the work of historians, or simply if the field is needed at all. So it is important to not only answer the question “how are digital tools reshaping the field of history?” but also to ask “why is it important to change it?” Fortunaley, the answer for both is the same. We need to change the field of history to bring the public in to challenge previous conceptions; and digital tools are the way to do this.

In the 1960s, a wave of historians began to study previously overlooked narratives like that of the enslaved and minorities of society. This was proclaimed to be the “new social history.” This supposedly revealed past misconceptions within historical narratives. However, I think we are still correcting our older, prejudiced views within history. Each and every day, with the help of historical tools, historians are finding previously hidden details or presenting history in a different manner in which the public can see the full picture. For example, digital tools were the basis of filmaker Errol Morris’s discovery of which photo of “The Valley of the Shadow of Death” came first by photographer Roger Fenton in 1855. One photo of the Crimena battlefield captures a scene of hundreds of cannonballs covering the landscape. However, another photo of the exact same landscape shows far less cannonballs, with many of them in a ditch. Many historains have concluded that Fenton initially moved cannonballs onto the road to create a more dramatic image. However, Morris is less quick to accept this psychological analysis and resorts to digital tools and experts in order to find which photo came first.

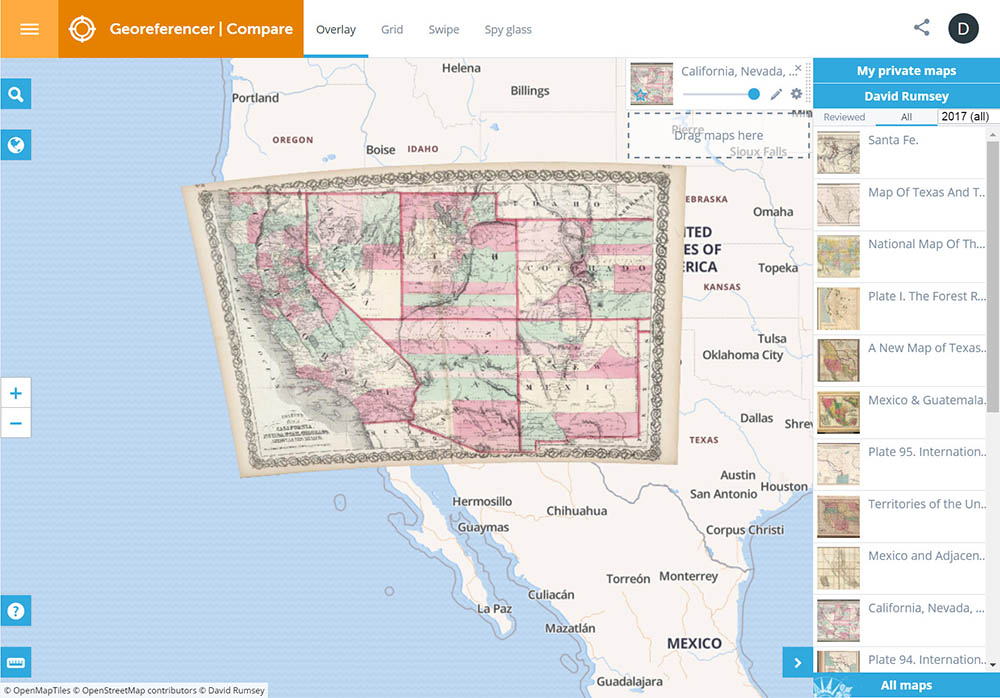

Even though the photo with the cannonballs on the road was in fact the second picture, Morris discovered that this was due to the law of physics that had forced the cannonballs to roll on the road.1 Therefore, utilizing digital tools and digital history strategies of sharing data and visualizations of the past with professional colleagues provide more of a buffer to falling victim of the human tendency to go with the obvious explanation based on preconceived notions. What seems obvious to us now would not seem obvious to actors of the past – and vice versa. We as historians must provide the tools and insight in order to overcome our own biases through lived experience. Even presenting historical research in just a different format, like Anne Sarah Rubin’s Sherman’s March and America: Mapping Memory interactive map will challenge everyone’s preconceived notions of a famous moment in history.2

The second half of how digital tools are reshaping the field of history incorporates the common man, meaning everyday people. Traditional academic history still remains unreachable for many members of our society. With academic journals and books only available through costly platforms like JSTOR that are only accessible to students or professors of a university, the so called “break throughs” of historians remains within our inner circle. Institutions like the University of Michigan are making steps towards making history more accessible for everyday people by making their publications public on the Internet. However, this academic focused historical rhetoric still proves to be inaccessible for people who did not receive a higher education degree in history. Simply publishing an ebook does not equate to the work of a digital historian. Products can be outside the realm of traditional books and articles. Reconfiguring how we present history is the key to making history personal for everyone, and then truly succeeding in the mission of new social history to bring light to forgotten narratives of the past. Timothy Compeau and Robert MacDougall’s historical game “Tecumseh Lies Here” is an excellent example of utilizing digital tools to engage people of all backgrounds. The game incorporates inquiry-based learning skills with primary sources that allow students to truly be their own historian.3

Historical games are far more accessible than academic journals that are predominantly read just within inner academic circles and exclude other members of society. Augmented reality apps like Niagara 1812 and Queenston 1812 appeal to a generation that cannot escape the digital age. Almost every person is connected to society through a digital manner and has been socialized to engage with others and our past through a digital platform.4 Instead of remaining stubbornly in the past by just publishing articles and books, historians should embrace this tide of digitalization. The same scholarly work applies – the same research, the same reading, the same corporation. However, digital tools can make our valuable work far more impactful on society through apps, engaging websites, and games rather than a book. Instead of only discovering a new historical conclusion through a book review released through JSTOR, digital history could result with these exciting new developments going viral on Twitter.

NOTES

- Morris, Errol. “Which Came First, the Chicken or the Egg? (Parts One to Three).” Opinionator: The New York Times (blog), September 25, 2007. https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/09/25/which-came-first-the-chicken-or-the-egg-part-one

- Rubin, Anne Sarah. “About.” Sherman’s March and America: Mapping Memory. http://shermansmarch.org/about

- Compeau, Timothy, and Robert MacDougall. “Tecumseh Returns: A History Game in Alternate Reality, Augmented Reality, and Reality.” In Seeing the Past with Computers: Experiments with Augmented Reality and Computer Vision for History, edited by Kevin Kee and Timothy Compeau, Online., Chapter 10. Digital Humanities: Digital Culture Books. Ann Abor: University of Michigan Press, 2019. https://www.fulcrum.org/epubs/5q47rq179?locale=en#/6/34[Kee-0017]!/4/2[ch10]/2/2[p176]/1:0

- Kee, Kevin, Eric Poitras, and Timothy Compeau. “History All Around Us: Toward Best Practices for Augmented Reality for History.” In Seeing the Past with Computers: Experiments with Augmented Reality and Computer Vision for History, edited by Kevin Kee and Timothy Compeau, Online., Chapter 11. Digital Humanities: Digital Culture Books. Ann Abor: University of Michigan Press, 2019. https://www.fulcrum.org/concern/monographs/70795899c