While history seems increasingly picked over for good topics, the future lies in adapting and utilizing new tools to expand the field. While to write on Lincoln traditionally more or less requires writing on the “sex life of Lincoln’s doctor’s dog,” to appropriate a phrase that Dr. Browning likes to use, there are alternatives.

The first is analytic reading. Rather than directly reading the wide cannons of early Victorian literature, or the titanic dataflow of modern elections, analytic tools provide tools to digest the material down into a more easily processed finished product.

First though, what do people actually consume. In looking at student news consumption, many students are primarily gathering their information through visual means. When looking at how many news sources there are, and how many things are clamoring for a student’s attention, this should not be surprising. An image can say a lot, while not taking nearly as much time to process as text or video.

New analytic tools create opportunities to do new history in well trodden fields. For example, Franco Moretti discussed the idea that rather than engaging solely with a core cannon of literary works, new history on the Victorian Novels would need to engage with a much more comprehensive set of books. Rather than reading line by line and word by word, engaging with the novels more generally requires adapting mathematical tools and turning them to other uses.

Additionally, new media has also begun its incursion into a collective historical past. The Internet as we know it today has its roots in the 1960s, with the first use of the technology in 1965, when two computers first talked to each other. One of the first major uses of this technology was email, which was developed in 1972, as a way to speed communication between far flung researchers. However, the Internet has spread far beyond simply a tool for researchers, and become a more widely spread entity. For example, Ian Milligan worked with a web host by the name of Geocities.com to develop an image of how different communities and websites presented themselves, and how they interconnected. This is effectively an anthropological study of the historical internet, ranging from family and children, to politics, education, and cars.

Beyond Victorian novels, and the Internet becoming history, there is also the problem of how we plan to do history going into the future. Modern events create far more chatter than almost any historical event. While much of it is going to be lost, it still provides a new historical challenge, to trawl through terabyte upon terabyte of data in order to develop a clear idea of the issues and discourse upon nearly any subject.

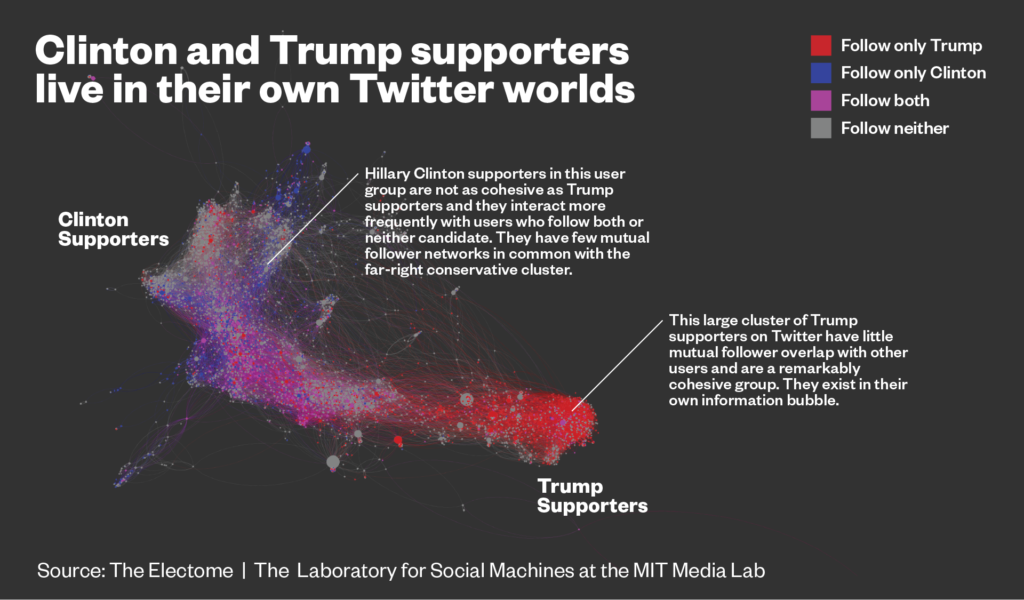

For example, in the great internet flame war of 2015-2016, aka the 2016 presidential election, MIT actually did a fairly large scale analysis of how the discourse on Twitter actually looked, called The Electome. This shared analysis of the election with a number of news sources, and showed some particularly interesting outcomes, not by reading tweets, but instead using keywords to find what was being talked about, and how it was discussed.

By boiling down the nearly billion tweets about the election into graphs, images, and datasets spread among a number of news platforms, the Electome managed to take an utterly overwhelming dataset and turn it into more easily analyzed information. When considering other modern events, such as the Coronavirus, similar tools will have to be used for analysis and evidence gathering.

However, this does not mean that the old methods of history are outdated or obsolete. Rather, they provide a different manner of information, and should be recognized as such. Older history creates opportunities to analyze particular news sources, or pieces of evidence closely and deeply, while analytic tools create a much more broad context.

One reply on “News, Research, and the Future of History”

This post really resinates with me, especially considering my current research. You bring up a good point, we can bring analytic tools to even older moments in history as well as apply older historic tools to more modern events. I am researching a little known women’s rights advocate, Myra Bradwell, and how she fit within the movement. One of the ways I am doing this is comparing the rhetoric between her newspaper and the newspaper of Susan B. Anthony. Perhaps for a future project, even dissertation, I could create an analytical graph that demonstrates the key words that appear within each newspaper. This would be an extremely useful way to visually see the differences and similarities within the movement.