Back in January, I wrote a blog post detailing what I believed to be the primary aspects of digital history, which I termed digital pedagogy, research, and history. [1] Now, at the end of the semester, coming back to that post, the class has both not covered what I would term digital history as a school of history, and covered things that I would not have thought of fitting, such as establishing a digital identity. Now, while I still believe that the school approach to digital history is an interesting idea, and worth of significant further study, it is also outside of the scope of the class, and instead I will focus on the former two ideas, pedagogy and research, although I will be approaching them in the opposite order this time.

In my personal experience, digital history research both makes things far easier, and simultaneously does not go nearly far enough. In my research for an eventual thesis on the Spanish American War, I have used, and attempted to use, quite a number of digital tools. In some cases, such as digital archives these have been incredibly valuable. For example, DigitalNC has offered up a large slice of the newspapers published at the time in an easy to search and easily readable format. [2] Furthermore, in this age of COVID-19, these digital archives are literal lifesavers, on top of being figurative ones the rest of the time due to presenting large numbers of digitized primary sources for use in papers and research projects. On the other hand, other tools are either too specialized such as Transkribus, or simply hard to get working properly, such as many of the OCR tools that I have tried to use. [3] However this is not intended as an indictment of the state of Transkribus, or of OCR. My use case is a particularly challenging one. Transkribus for example is intended to use a large selection of a single person’s writing to create a recognition frame in order to transcribe it into print text. I wanted a system that would allow me to take a bare handful of letters and make them easier to read, which is a much more challenging problem, because most of my writers only sent maybe half a dozen letters, if that, during their service in the Spanish American War.

To discuss more generally however, digital research offers up new ways to access, interpret, and share information. With access, while digitization is highly expensive both in immediate and ongoing costs, it makes preserving documents easier, and makes them far more accessible. This is not only because I can connect to them anywhere that I have an internet connection, but also because the process of preparing the documents for digitization often makes the materials themselves more readable. [4] With interpretation, the first and last gate has always been the historian. While new tools can offer new insights, they cannot replace good judgement. For example, in the case of Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman’s Time on the Cross, they used large selections of data and computer modeling to attempt to divine the real experience of slavery. While they made some interesting points on the economic viability of slavery, they utterly misrepresented and mangled their interpretation of the slave experience. [5] At the same time, this is not a problem of digital modeling, and digital interpretation, but of the historians doing the work. Tools like Voyant create opportunities to examine language in a more fine toothed manner, and offer new ways to engage with well trodden fields. [6] Finally, sharing information is really the most revolutionary aspect. While some historians are too enthusiastic about its revolutionary potential, the ability to share a work in progress means that the time for peer review does not begin during the publication cycle, but long before it. [6] However, at the same time, traditional books and journals offer fixed points in time to maintain a historiography, rather than simply changing the pieces that don’t fit in the interpretation any more.

The other half of the digital history question is pedagogy. This is again a number of parallel paths, effectively, teaching history directly with digital technology, teaching how to do history with digital technology, and finally distance teaching.

In teaching history directly with digital technology, much like the rest of teaching history, there is no substitute for a dedicated, interested, and engaged teacher. In the Tecumseh Lies Here ARG for example, no amount of packaging and preparation was able to capture the impact that a small team, acting and reacting based on live information was able to create. [7] Games in various forms have long been a part of teaching, and offer significant advantages, primarily by being able to simulate and approach complicated topics by baking those ideas into the game design, and stimulating the competitiveness inherent in play to master those topics. [8] Beyond teaching with technology, teaching how to use technology is likely even more important. At its most basic, history in the modern day is not about knowing facts and figures. That Christopher Colombus set out across the Atlantic Ocean in 1492 is really an irrelevant factoid. Modern history, especially with Google and other search engines, is more a process. Inquiry, research, and verification are the tools that the modern history classroom needs to leave the student with, not the stale and well trodden facts and figures. Most modern students have access to research tools in the classroom, and have the ability to begin to put it together. [9] Similarly, teaching students to build and maintain their own websites is a key life skill that falls relatively neatly into the goals of the humanities. [10] This teaching how to do history can also put student historians into practice, for example the University of Edinburgh’s Wikipedia editathons. [11]

Finally, there is distance learning. Especially in this age of COVID, distance learning is the key challenge for educators, and something that this class has leaned into. While programs like Zoom, Skype or Discord can help, fundamentally, learning at a distance requires a reorganization of how teaching works, and must include trusting students to do projects independently.

Overall, I see digital history as more evolutionary than revolutionary. While digital histories offer new tools for nearly every aspect of the profession, and ones that I fully intend to make use of, the tools do not change the underlying discipline as a whole. In this class, I have used the same skills and approaches as I have in any other, but have added new tools and understandings of how I can use those tools to an already existing toolbox.

[1] Chamberlain Silkenat, “Start of Semester Understandings” Digital History, Jan 28. https://digitalhistory.rwanysibaja.com/publishing/start-of-semester-understandings/

[2] “North Carolina Newspapers.” DigitalNC. North Carolina Digital Heritage Center http://www.digitalnc.org/collections/newspapers/.

[3] “Transcribe. Collaborate. Share…” Transkribus. https://transkribus.eu/Transkribus/; “Download OCR Software.” SimpleOCR, January 29, 2020. https://www.simpleocr.com/download/.

[4] Emma Skinner, “Letters of Note: Preparing the Prize Papers for Digitisation,” UK National Archives, April 30, 2020. https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/letters-of-note-preparing-the-prize-papers-for-digitisation/; Archives @ PAMA, Region of Peel. “Why Don’t Archivists Digitize Everything?” Archives @ PAMA, June 1, 2017. https://peelarchivesblog.com/2017/05/31/why-dont-archivists-digitize-everything/.

[5]Robert William, Fogel, and Stanley L.. Engerman. Time on the Cross: the Economics of American Negro Slavery (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1995).

[6] Stephen, Sinclair, and Geoffrey Rockwell. “Voyant Tools.” Voyant Tools. https://voyant-tools.org/.

[7] Timothy Compeau, and Robert MacDougall. “Tecumseh Returns: A History Game in Alternate Reality, Augmented Reality, and Reality.” In Seeing the Past with Computers: Experiments with Augmented Reality and Computer Vision for History, edited by Kevin Kee and Timothy Compeau, Online., Chapter 10. Digital Humanities: Digital Culture Books. Ann Abor: University of Michigan Press, 2019. https://www.fulcrum.org/epubs/5q47rq179?locale=en#/6/34[Kee-0017]!/4/2[ch10]/2/2[p176]/1:0

[8] Jorit Wintjes,“‘Not an Ordinary Game, But a School of War’ Notes on the Early History of the Prusso-German Kriegsspiel,” Vulcan: Journal of the Social History of Military Technology 4, no. 1 (January 2016): 52–75.

[9] Joseph D. Galanek, Dana C. Gierdowski, and D. Christopher Brooks. “Experiences with Instructors and Technology,” Educause, 2018. https://www.educause.edu/ecar/research-publications/ecar-study-of-undergraduate-students-and-information-technology/2018/experiences-with-instructors-and-technology

[10] Sara Grossman, “Web-Hosting Project Hopes to Help Students Reclaim Digital Destinies.” The Chronicle of Higher Education Blogs: Wired Campus (blog), July 25, 2013. https://www.chronicle.com/blogs/wiredcampus/web-hosting-project-hopes-to-help-students-reclaim-their-digital-destinies/45035

[11] Martha Saxton, “Wikipedia and Women’s History: A Classroom Experience.” In Writing History in the Digital Age, ed. Jack Dougherty and Kristen Nawrotzki, 86–94. (Digital Humanities: Digital Culture Books. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013) https://muse.jhu.edu/chapter/1030707

Author: ChamberlainS

During my research into the Spanish American War, I found a collection of images taken by an amateur photographer in the 1st Battalion of the 1st North Carolina Volunteers. These images had very little in the way of explication and context, so I have attempted to take a sample of these, and see what I could analyze from the composition and subject matter of the images. All the images were taken in a four month period in early 1899, when the unit was in Cuba, but that is it so far as contextualization.

https://photos.app.goo.gl/v7phvvhJZe5RG9G16

History Games

The Bannockburn visitor’s center is on an open field. Looking out from the visitors center, to the south the field curves gently down into the Bannock Burn. In the north, there is the town, and St. Ninian’s church, and beyond St. Ninian’s there is Stirling Castle, high on a hill.

It is not Gettysburg, which has been marked by every faction as an ongoing battle over the memory of the American Civil War. It is not the beaches at Normandy, still marked by concrete bunkers. Its only markers are a statue of Robert the Bruce, and a memorial rotunda.

But, despite the lack of material, I remember this battlefield, and this visit. Because it taught the history with a game. After going through the museum, we were brought into a circular room, with a table on the centerpiece. The terrain of the battlefield was molded onto that table, and projected from above were banners of each of the lords leading troops on the battlefield. There, each of the people was given command of a few banners. It was my family, and as I remember one other. Archers, Infantry, Knights, and the Scottish side got Schiltrons. In that battle, my team was fairly passive, and so I ended up taking general command. In the battle itself, the English drove forward, smashing across the bridge on the Bannock Burn under the cover of a withering hail of arrows. While the Scottish defenders held, the battle was won, as a single unit of archers pounded Robert the Bruce’s formation until the man fell, riddled by clothyard shafts.

Unlike most battlefields, where we tell the stories of those long dead, there, we created a story of our own. A clearly ahistoric one, given that the Scottish suffered from a divided command, while the English were driven forward in a single minded assault, but a personal story. In reality, the English lost, decisively, and Scotland would remain its own country for centuries more.

Similarly, in Tecumseh Lies Here, the game is ahistoric. The setup, a shadowy conspiracy leading them to race through books and around historic sites is a staple of cyberpunk and television shows. However, at the same time, the key element of the game, getting participants to learn history by actually doing history, is something that has real, genuine educational value. However, it has its limitations. Especially the amount of work that goes into making a single shot experience. Throughout Timothy Compeau and Robert MacDougall’s account of the game, the piece that keeps cropping up is just how much work went into the experience, and how little success they had in adapting an ARG into something that could be replicated in classrooms across Ontario, let alone beyond it. The solution they found, turning it into a augmented reality experience, lacks the interactivity to really be called a game, at least in my opinion.

Offering more promise in crafting games to teach history are the Niagara and Queenston 1812 experiences. Rather than going into a comprehensive ARG, the games are smaller experiences, using digital technology to enhance physical locations, specifically allowing historic sites to put far more documentation and manuscripts into the hands of the people at the site than would be possible with conventional tools. How effective these AR tools are in actually teaching history, or creating historically engaged people is still questionable.

Overall, the position of games in teaching history is still open to contention. I believe the future is not so much in using games to teach the processes and methods of history, as it is in making history personal. Whether that be through a self contained experience as at Bannockburn, or the more open designs of Niagara and Queenston, games offer the ability to not just experience history as a passive observer, but to engage with the events, and tell the story on the player’s terms.

While history seems increasingly picked over for good topics, the future lies in adapting and utilizing new tools to expand the field. While to write on Lincoln traditionally more or less requires writing on the “sex life of Lincoln’s doctor’s dog,” to appropriate a phrase that Dr. Browning likes to use, there are alternatives.

The first is analytic reading. Rather than directly reading the wide cannons of early Victorian literature, or the titanic dataflow of modern elections, analytic tools provide tools to digest the material down into a more easily processed finished product.

First though, what do people actually consume. In looking at student news consumption, many students are primarily gathering their information through visual means. When looking at how many news sources there are, and how many things are clamoring for a student’s attention, this should not be surprising. An image can say a lot, while not taking nearly as much time to process as text or video.

New analytic tools create opportunities to do new history in well trodden fields. For example, Franco Moretti discussed the idea that rather than engaging solely with a core cannon of literary works, new history on the Victorian Novels would need to engage with a much more comprehensive set of books. Rather than reading line by line and word by word, engaging with the novels more generally requires adapting mathematical tools and turning them to other uses.

Additionally, new media has also begun its incursion into a collective historical past. The Internet as we know it today has its roots in the 1960s, with the first use of the technology in 1965, when two computers first talked to each other. One of the first major uses of this technology was email, which was developed in 1972, as a way to speed communication between far flung researchers. However, the Internet has spread far beyond simply a tool for researchers, and become a more widely spread entity. For example, Ian Milligan worked with a web host by the name of Geocities.com to develop an image of how different communities and websites presented themselves, and how they interconnected. This is effectively an anthropological study of the historical internet, ranging from family and children, to politics, education, and cars.

Beyond Victorian novels, and the Internet becoming history, there is also the problem of how we plan to do history going into the future. Modern events create far more chatter than almost any historical event. While much of it is going to be lost, it still provides a new historical challenge, to trawl through terabyte upon terabyte of data in order to develop a clear idea of the issues and discourse upon nearly any subject.

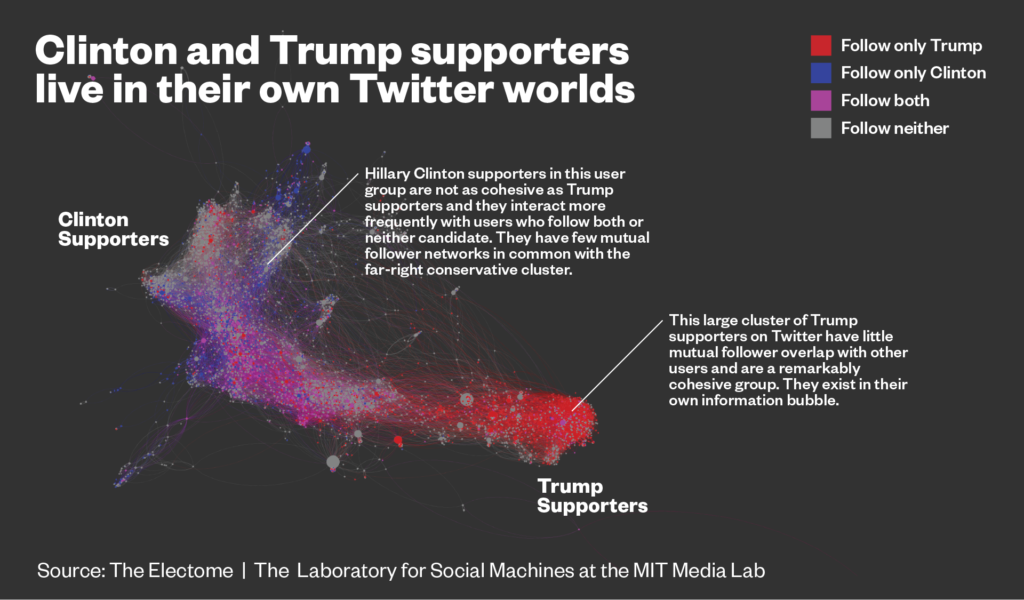

For example, in the great internet flame war of 2015-2016, aka the 2016 presidential election, MIT actually did a fairly large scale analysis of how the discourse on Twitter actually looked, called The Electome. This shared analysis of the election with a number of news sources, and showed some particularly interesting outcomes, not by reading tweets, but instead using keywords to find what was being talked about, and how it was discussed.

By boiling down the nearly billion tweets about the election into graphs, images, and datasets spread among a number of news platforms, the Electome managed to take an utterly overwhelming dataset and turn it into more easily analyzed information. When considering other modern events, such as the Coronavirus, similar tools will have to be used for analysis and evidence gathering.

However, this does not mean that the old methods of history are outdated or obsolete. Rather, they provide a different manner of information, and should be recognized as such. Older history creates opportunities to analyze particular news sources, or pieces of evidence closely and deeply, while analytic tools create a much more broad context.

The Importance of Trust.

In T. Mills Kelly’s “True Facts or False Facts,” one of the key elements in the success of the original hoax was its riding on academic trust networks. She claims that those taken in “didn’t do their jobs as historians.” I believe otherwise.

Academic trust networks are a vital part of actually being able to do the job as a historian. Simply put, there is too much history, and too much history being made, to do anything else. With citations, in theory, any historian can track any book or article all the way back to the primary sources. However, that is, in many cases, not practical. As a case in point, I have a random book off of my shelf, Timothy Tyson’s The Blood of Emmett Till. The book uses endnotes, and in the 13th citation of chapter 17 “Protest Politics,” Tyson cites the New York Times, and I can go, and find the article. However, not all of those sources are as easy to find. The second citation of the same chapter goes to an article found in the Carl and Anne Braden papers, which is held by the Wisconsin Historical Society. In the latter case, I have to trust that Tyson is telling the truth both about what the article says, and where it is held.

There is more to academic trust than simple citations. As historians and academics, we are often forced to take on questions that do not fully fall into our self defined niche. That can be covering another teacher’s class, trying to answer a student’s oddball question, facing down the public in an open forum, or trying to follow the implications of a question we raised ourselves. . With these questions, being able to answer well often requires some significant degree of trust in the historians around us. No historian has the time to fact check every claim made in every book. In point of fact, no historian has the time to read every book. So, to try and combat the never ending flood of publications, informal trust networks form in order to pass relevant important information to other historians, and gain useful information ourselves.

However, this does not make the historical hoax as an exercise any less valuable. While “”In war-time, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.”* In history, a lie often requires a bodyguard of truths. In order to be convincing, the students had to not only learn the basic skills that any introduction to history teaches, but also how to write convincingly, how to weave together sources to create a narrative, and how to use multimedia tools effectively. Any good historian can create a convincing historical hoax, because it requires the same tools of research, writing, and development in order to create a plausible narrative. By teaching how to lie convincingly, Kelly was also teaching how to tell the historical truth in an engaging and meaningful way.

*Winston Churchill: The Second World War, Volume V : Closing the Ring (1952) 338.

One of the main challenges of the modern day is the conflict between establishing a middle ground between protecting student’s personal data, and creating means for that student to market themselves and leverage the social media environment for their own ends.

On one hand, there is the fact that schools and universities are the formative times of almost everyone’s early lives. Places like Appalachian State collect vast reams of information relating to student health, engagement, grades, and interests. Much of this is privileged information under FERPA (The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act), and there have been numerous attempts to further restrict what can be shared. Here, I see a very real concern about the use and utility of student information. While certainly not as immediately valuable as a credit card number, or banking information, it is an extremely broad and deep set of information, which, if obtained, can be exploited for profit. However, some of the proposed laws are likely too restrictive, and may well hinder actually good research, such as work that has exposed problems with traditional education, including that “poor, nonwhite and non-English-speaking children have been educated inadequately by their schools.” (Susan Dynarski) This is a place where both privacy activists, and educational groups with an interest in using school data to improve outcomes have valid, and viable points.

On the other hand, managing a digital footprint is a vital life skill. A website offers a platform for ideas, a place to put an array of personal details, and a demonstration of personal skills. This is one of the places where the classroom can reach out beyond the four walls and the power point, and give students a piece of work that will stay useful long past passing the class or graduating the school. Looking at the program developed by University of Mary Washington, the key piece is that it is a student’s space, built around a framework offered by the university, but shaped by each student’s unique needs, desires, and goals. The school is, in effect, providing added value, and validation to the student, on top of the education needed to build, maintain, and add to the site.

Beyond the advantages of schools offering benefits beyond the classroom, the crafting of one’s own personal digital space is a fundamental piece of digital citizenship. Most of the internet exists to make the people serve it, through advertising, through data collection, and through social manipulation. The creation of personal, and personalized digital spaces creates the freedom to express feelings, ideas, and work without the limitations of commercial and commercialized space. Digital citizenship is often tinged with fears of doing or saying the wrong thing, and then being haunted by it forever, because on the internet, nothing really goes away. While this is a useful thing to know, it is far from being the be all end all, or even the most important piece of citizenship in a digital world. More critical is trying to use that digital world to make a space where we can all live.

Finally, social media is an important part of networking and publicizing historical work. While the limits of twitter make it a terrible platform for expressing historical ideas or engaging in debate, it is perfect for advertising events. Looking more deeply at twitter, it serves as a tracking tool for people wanting to live as historians. As Jason Jones put it “how often people go to panels, when they visit the book exhibit, when they need downtime, whether they’re still working on papers, and more.” Much of the historian’s social craft is obscured, and Twitter is one piece of raising the curtain. Similarly, other social media such as Facebook works to build a historical community, despite its privacy issues.

For technology and teaching, there are, as I see it, three main ways that it can be approached. First is classroom enhancement, which uses digital tools to improve learning in a classroom environment. Second, is what might be termed classroom outreach, taking lessons learned in the classroom, and turning them into public utility, such as Martha Saxton’s Wikipedia project. Third is classroom replacement, which is what the rapid spread of corona-virus has forced. This is in some ways the most challenging of the three, because at one time, the technology has to be accessible, user friendly, and engaging while maintaining academic rigor.

With classroom enhancement, the fundamental challenge is how to use the expanded toolkit without creating distractions for the class. While using personal devices to record the class, take notes, quickly search for relevant information, or assist with disabilities is a good starting place. (Educause: Experience With Instructors and Technology) There is far more that can be done.

In a personal example, Dr. Fredette uses ASULearn to give quizzes in class. These are taken with your personal device, and then I can grade them digitally. These are usually two short answer questions, or multiple choice. The advantage here is not so much to the students, but rather to the professor and teaching assistant, because it makes it so that I don’t have to keep track of, and faff around with a giant pile of paper, and ensuring that every paper gets back to the right person. This system is still fairly manual however, and other people, such as Amy Cavender have done a far more automated system, using google forms to automate what might well be called drudge grading. However, there is more that can be done to enhance the classroom than simply grading. One example is the use of instant polling, such as PollEverywhere, to guide lecture and presentation. The educator can ask a question, and then rather than selecting a few (un)fortunate souls to give answers, the entire class can respond, using a word cloud, multiple choice, or other data visualization to find either gaps in the information, or look at classroom engagement as a whole. Similarly, the collaborative aspects of Zotero create an environment for a class to find interesting primary and secondary source material, and more importantly, give the teacher a way to personalize the search for useful, reputable sources, and intercept bad sourcing before the paper. The key idea with all of these however is that they do not fundamentally change the classroom, but rather attempt to streamline or enhance already existing tools of teaching, or solve long lasting issues with how teaching works.

Second is classroom outreach. Most classroom work does not produce anything of real lasting value. A paper likely only matters to the student and the professor. A project is a fleeting moment of creation, but soon forgotten. Classroom outreach attempts to change that. Rather than the value in the assignment being the skills learned while doing it, classroom outreach projects attempt to create value long after the actual assignment is completed. To return in more detail to Martha Saxton’s students, their expansions of women’s history gave them means, motive, and opportunity to engage in a broader public discourse about the role of women in history and how to present it to a broad public. While much of their work has not survived long term, it is in many ways a more meaningful approach to doing history than simply another paper, because it puts them in direct contact with a historical public, and the biases and limitations of that population. One key takeaway from the article, at least when it comes to women’s history, is just how little it matters to the editors of the source. Another example of the uses of Wikipedia comes from the University of Edinburgh, which every year hosts an “innovative learning week” (often disparaged as: innovative skiing week). In 2015 (my freshman year at the university, although I was not involved in this particular event), one of the events as part of the ILW, was a Wikipedia editathon on the history of the Edinburgh Seven, which were the first women admitted to a UK medical school. This experiment showed many similar things to the key problems faced by Saxton’s students, and many similar themes. One key piece is that this project gave students a sense of agency and ownership of the ideas that a standard paper likely does not. While Wikipedia is not the be all and end all of classroom outreach, it is one of the most accessible forms of it. This outreach is really about empowering students to go beyond simply learning the skills of the trade, and moving into actually applying them.

Finally, classroom replacement is not a new idea. Distance learning has been part of the educational system for all of living memory. (Holmberg, Research review: The development of distance education research) However, the modern challenges of COVID-19 is forcing a reconsideration of how to do this effectively for a majority audience. While tools like the Learning Management System offer a high degree of utility for students, it is not a replacement in value for personal interaction and engagement with professors. To maintain that source of value, new tools must be adopted. (Many of these examples come from entertainment rather than strictly academic backgrounds, because my experience with purpose built tools is effectively zero.) These tools must be able to balance between class size, interactivity, and ease of use. For example, with relatively small classes, such as this one or Dr. Silver’s Environmental History, tools like Zoom, or Kast, would likely work best. Zoom is more oriented towards discussion, while Kast, or Netflixparty, or one of a number of similar services, create environments to both watch and discuss media in real time. So, for example, taking the CSPAN feeds of Gettysburg College’s Civil War Institute, or for a media class, engaging while watching John Carpenter’s The Thing. These tools mean that the class can engage and react in real time with the professor. With larger classes however, other tools will likely work better. Discord for example, creates a space for asynchronous class discussions, while also allowing a teacher to stream lectures or other content. Twitch is another live streaming platform, which is optimized for relatively large audiences. It does this by giving audience members a relatively narrow flow of outgoing information, while streaming video and audio to all of them. This platform is already being used for non academic political discussion, for example recent Democratic Party primary debates, where streamers commented over the debate. However, with the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, this tool is almost certainly better as a lecture substitute, where the material is either in the public domain, or is original to the lecturer. As a lecture tool, the way I would see going about it would be an open live stream, and sending the link out to the class, after which it would follow as a standard lecture, but one with a sidebar interaction to react and discuss the points being made.

To attempt to sum up this sprawl, digital teaching is in some ways a transformation of how teaching is done, and in other ways is simply taking existing ideas and attempting to use tools to just do it better. In all cases, however, the goals remain the same. The purpose of teaching is to provide people with the tools, drive, and interest in conducting the processes of history for themselves.

(NB: This is not really intended towards a grade, but rather because I found this to be an interesting topic, and wanted to take a bit more time to look around and find more about the material.)

The Problem of Journals

I specifically want to discuss, and to an extent push back against one of the articles for today, specifically, Reinventing the Academy Journal. The piece presents six primary goals. First, to ensure interoperability with the tools of digital scholarship. Second, as creators and curators of digital reputability. Third as curators of a broader selection of works. Fourth is actually an abandoning of their position as exclusive curators of works. Fifth is to make their process of peer review more inclusive. Finally, the sixth is to extend the timelines of peer review, and engage with history as an ongoing process.

Now, some of these I can accept as they are given. For example, the third selection is one of the best in the entire list. Having resources such as syllabi, presentations, and other educational materials being more accessible provides value to new professors, and professors teaching new classes, as it creates access to a shared pool of useful pieces. Now, some journals already do this. For example, The History Teacher, which, back in may of 2009 published an article by Judkin Browning on his yearly water balloon wargame. Of course, the journal article only focuses on a single piece of the class, rather than looking at its position as a part of the class as a whole. Equally, the interoperability of journals and the tools of digital history is simply making the tools available more functional.

However, where I believe that I must push back is on the idea that journals can become some measure of digital credibility. The first key issue is that digital spaces routinely, gleefully tear down institutional credibility. No institution can ensure that their entire body of work is without fault. Beyond that however, is the problem that Journals serve a valuable role in a slower form of history than digital spaces. Digital spaces are great for fast history, where there is both less distance between the analysis and the primary sources, and constant changes. Journals, and really books, provide a space where history becomes fixed. This provides continuity, and a marking of the historiography. Even when wrong, or disproved, or out of fashion as an interpretation, their role as fixed points makes them a useful ongoing piece of a broader historical practice. The impermanence of digital spaces means that a full shift over to an agile academy will leave a gap in the historical practice, something which must be avoided for the sake of future generations of historians.

To look to the future of the academic journal, I see them filling many of the same roles as they do today. Fewer reviews, and more shorter pieces of academic writing, but not trying to intrude into the digital sphere. The primary innovation that would increase their value is in being hybrid models, akin to the dissertations outlined by Lincoln Mullen. A short academic monograph paired with some pieces of digital scholarship.

Finally, there is the ongoing review. This is a piece where the academic presses are simply not the right context for the affair. The academic presses are a useful piece, but are, simply not the right context. Rather, this is a place where an academically backed forum, or other collaborative tool, would suit the needs of the historical community far better, with the Journal being more of a final stamp of approval for completed projects.

Jo Guldi’s proposals all appear to be fully in good faith, and some of them are ones that I am fully on board with. However the key flaw is that not all of them serve the same purpose as the traditional academic presses. Rather, they need new forms of academic cooperation and new academic institutions need to be made to engage with the next generation of digital history.

(NB: I am not writing this for a grade, but instead as a tool to help me see how my understanding of what Digital History is, and what can be done with it changes over the course of the semester, and am publishing it because I think it might generate some interesting discussion.)

Digital history, fundamentally, breaks down into three pieces, not all of which are related to any great degree. First is what could be called Digital Pedagogy, which concerns the use of digital technologies to enhance learning, such as long distance courses, blogging, websites and such. Second is what I may term digital research, which focuses on the utility of digital technologies, such as portable cameras, digitized archives, and beyond that the ability to contact and engage with historians on research questions and share research material. However, gathering and sharing is not the extent of the influence of computers and the internet. Rather, computers also allow an engagement with information in more quantitative, rather than qualitative methods. Finally, what I may term digital history proper. Rather than a question of doing history using technology, it is a history of digital spaces.

Digital education has been a question facing the academic world for well over a decade, and is the domain not only of marginal institutions, but even academic centers, such as the University of Edinburgh. These provide a new way to engage with students, not just in the classroom, but beyond it. However, outside of the path of the direct academic teaching, there are also some 10,960,000,000, pages searchable by Google that to one degree or another touch on history. This online presence is the pathway that the vast majority of the population engages with historical topics.

Digital Research really represents a fundamental change in how research is done, what is useful in research, and how we as historians access resources. First, it globalizes what research can be done. Rather than solely focusing on local issues, and what foreign assets can be found in nearby archives, or making expensive trips around the world, the digital age has made it so that vast collections of materials can be brought to bear from anywhere with an internet connection. Computers also create the ability to engage more fully with large amounts of data, such as looking at day to day production at a particular factory, or rosters of Civil War regiments.

Digital history is a history that engages fully with the questions of digital spaces. At the risk of becoming too political, the 2008 campaign had a significant investment in digital spaces, what David Carr of the New York Times described as “a network of supporters who used a distributed model of phone banking to organize and get out the vote, helped raise a record-breaking $600 million, and created all manner of media clips that were viewed millions of times. It was an online movement that begot offline behavior, including producing youth voter turnout that may have supplied the margin of victory.” This was not a one off event, but rather one piece of a much larger opening of a political and social debate. Equally, the GSRM movements (Gender, Sexual, and Romantic Minorities) movements gained significant ground, in part due to the ability of the internet to create communities and link individuals with similar conditions. While these topics are somewhat too close to ourselves to be engaged with in academic histories, the question of how and why digital spaces have shaped modern history is still one that should be considered, especially for the next generation of teachers, who will likely be guiding the research into these fields.

Digital publishing combines a number of advantages and disadvantages. While worth exploring, the nature of digital publishing makes it a better platform for some forms of history than others. While a common concern seems to be the question of whether blogging is scholarship or not, such as in Cummings and Jarrett’s piece, “Only Typing? Informal Writing, Blogging, and the Academy.” I personally find that to be an issue that lacks in nuance and imagination. Blogs, and digital publishing generally are not challenges to traditional historical methods. Much like Facebook cannot replace meeting people in real life, so to can blogs and websites not replace conferences and seminars in the real world. Rather, it is a fundamentally different pursuit, one that can bring in new audiences who are not engaged by traditional historical work.

Digital publishing, and presenting work in the digital sphere has a few key components that make it better in some ways than traditional historical works. The first critical element is that digital publishing can engage far more fully with primary sources. Unlike a conventional book, which nearly always must cherry pick quotes and phrases, with a few extended sections, digital publishing can include pictures of the primary sources, and, with a little more effort, transcripts. Second, digital publishing is far more agile. With a physical book, once the work is printed off, there is little that can be done to make changes and corrections. Comparatively, for a digitally published work, there is an ongoing peer review process throughout the life of the work. This cycle of posts, comments, and revisions creates opportunities for websites and digitally published media to reflect not just a snapshot of a historians thoughts at the end of the process, but rather an ongoing conversation between the readership and the historian. Third, digital publishing allows for far more informationally dense work. Rather than having to spread all of the information out within the constraints of a page, digital publishing, such as Digital Harlem’s ability to map out hundreds of events that all occurred within a month in and on the borders of New York City’s Harlem neighborhood. (http://digitalharlem.org/)

However, there are also disadvantages. First and most critical is that web systems are to a great degree fundamentally temporary. Even for information that is still somewhere, the links get lost or disconnect, changes on the technical back end can break integrations. Secondly, digital history often breaks the narrative arcs that traditional history relies on. James McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom works on narrative arcs both within chapters and across the entire work. When that narrative is hyperlinked, readers forge their own path, walking through pages that catch their interest. Further, each piece is often shorter, for example the Ted Talks usually range between about seven and twenty minutes, far shorter than common historical documentaries.

For historical work, digital history straddles the lines between popular, public, and academic history. While limited based on platform, digital publishing offer a pathway to present primary sources, examine secondary works under a historian’s lens, and publicize the historian’s craft. Beyond that, the internet can be used to present incomplete ideas, or simply interesting historical individuals. However, the most critical use of this public environment is actually to engage with the parahistoric works that see far more wide distribution than even popular historical works.

First however, some terms need to be explored, specifically, popular, public, academic, and parahistoric. While popular history is often little more than a snarl word in academic circles. However, it does provide a significant advantage in engaging mass audiences. As Wikipedia describes it, popular history “emphasizes narrative, personality and vivid detail over scholarly analysis” However, this style of history is also gripping, bringing in people who simply want a good story. Public history comparatively, is done by trained scholars, in attempts to reach out to a public audience. Academic history is primarily analytical. While bringing new or rediscovered primary source documents is a key piece of the historical system, academic history primarily relies on analysing, comparing, and interrogating the accuracy of source materials.Finally, there are the parahistorical works. These cluster around history, using historical themes, historical assets, without really explaining the significance. A clear example of this is the Call of Duty series, which engages with history, showing critical battles and high resolution images of the weapons and uniforms (most often of world war 2) but does not really draw on a real sense of history. It is these parahistorical works that provide the clearest challenge to traditional methods of history. First, they are popular. To use Call of Duty as an example, Call of Duty: World War 2’s multiplayer on Steam alone had some 56,174 concurrent players, and the game overall, had sold nearly 20 million copies as of February 2019. However, it is also fast moving. Within traditional history, the reaction and replies can often take months, or even years to formulate. By the time the historical sphere could react, the parahistorical sphere had already moved on to new media.

And that is where the advantages of digital history are maximized, while the disadvantages are comparatively minimized. It does not matter that a link has broken three years down the line, because the audience has moved on two and a half years ago, and is looking at different content. While traditional historical audiences demand footnotes and endnotes, a parahistorical audience often will not follow those footnotes, but may well follow a link.

A blog or other web project creates a space where some of the articles can relate those interesting personal stories of history, the ‘believe it or not’ pieces that drive much of popular history, while combining it with academic rigour by paralleling those with digitizing primary sources and more analytical articles. While traditional academic approaches are often difficult to approach, and require careful reading even for trained scholars, the informality of blogging and online spaces allow for history to be more approachable than either walls of verbiage or simple recitations of places and dates. Blogging, and online history more generally needs to be a gateway from a popular history to more academically driven approaches. Rather than being purely a side project, or a way to promote the “real” history books, a blog can serve as a place of historical development.This is not to say that real, serious, historical work cannot be done in the digital sphere, but rather that digital history opens opportunities to engage with communities that the standard practices of history do not reach.